Digging Discovery: How Organic Material Accumulation is used to Classify Wetlands at the Wetland Centre

/What makes a wetland a wetland? How can you tell where one wetland class ends, and another begins? The material under your feet can help you discover the answers to these questions! To better understand the classes of wetlands present at the Wetland Centre at Evergreen Park and to refine the original wetland boundary mapping developed in 2016, Ducks Unlimited Canada (DUC) collected peat depth and vegetation data at sampling sites across the Wetland Centre in July 2022.

Rick Murray (DUC Conservation Programs Specialist) led the assessment and was supported by the Grande Prairie Junior Forest Ranger Team and DUC staff member, Madalyn Barnfield.

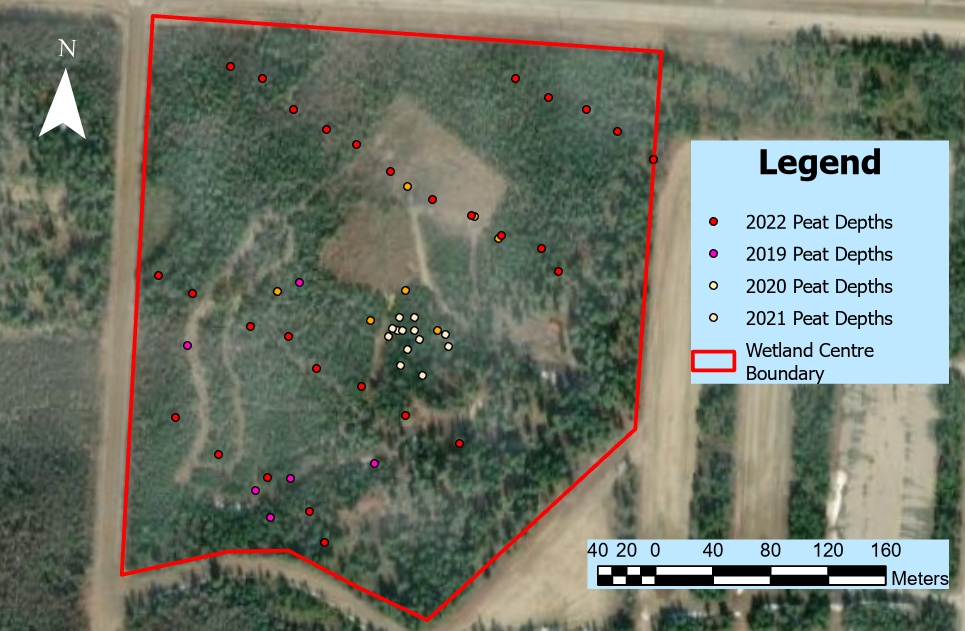

Using a hand-auger with multiple extensions (that reach depths of 3.2 m) and our trusty wetland classification guidebook, the team collected soil and vegetation data from 29 sites in 2022, to add to the 27 sites already done from 2019 to 2021.

Peat depths locations recorded at the Wetland Centre from 2019 to 2022.

Of the sites completed in 2022, 19 were “simple assessments” where we recorded organic material depth and a general observation of plant species at the site. We also completed ten “detailed assessments” where we recorded : organic material depth, decomposition rate (i.e., Von Post rating), texture of the mineral underlying the organic material (e.g. sand, silt, clay, etc.), indicators of water influencing the soils (e.g., mottling, gleying [see Photos below]), type of plants, plant cover height, and surface or below ground water depths.

So how exactly can we use this information to tell if we’re in a wetland? There are a few key indicators that can be spotted when soils are wet for long enough. These indicators include the accumulation of organic material (deep peat!), soil mottling, and gleying. If you have any of these soil indicators, it’s time to get your guidebooks out to take a closer look!

Prominent mottling in Soil (Orange colour splotches; left Photo), gleying in soil (dull dark gray, bluish tinge colour; Middle and Right PHotos)..

An accumulation of organic material is often a sign that you are in a wetland. In addition, the depth of organic material can help determine whether an area is a peatland (bogs and fens; >40 cm) or mineral wetland (swamps, marshes, shallow open waters; <40 cm).

Various fen and swamp soil samples laid out to show the different layers of organic material (darker colour) prior to reaching the underlying clay (Note: The top of each photo represents the ground surface).

Let’s take a look at what we found at the Wetland Centre to see if our assumptions match our results:

Five sites were Upland (zero/minimal organic material accumulation, no mottling or gleying)

Nine sites were Wooded Coniferous Swamp (ranged between 20 to 150 cm organic material accumulation with a Von Post of 5 to 7)

Three sites were Shrubby Fen (ranged between 175 to 265 cm organic material accumulation; no Von Post recorded)

Twelve sites were Wooded Coniferous Fen (ranged between 75 to 245 cm organic material accumulation with a Von Post of 4 to 5)

organic material depths (cm) recorded at the Wetland centre in 2022

“But wait!? Some of these swamps have >40 cm of organic material; shouldn’t they be classified as fens?” You’re right, but relying on organic material depth alone can be tricky when determining the wetland class. Another indicator to consider when determining whether an area is a peatland or mineral wetland is how decomposed the organic material is. Weakly decomposed organic material is typically associated with bogs and fens while highly decomposed organic material is typically associated with swamps, marshes and shallow open waters.

Examples of weakly decomposed (left; von post 3) and well decomposed (right; von post 6/7) organic Material samples

So, what happens when your depth says peatland (fen) and your state of decomposition says mineral wetland (swamp)? The answer comes down to a judgement call. In this case, although four of the swamp classified sites at the Wetland Centre had >40 cm of organic material accumulation (65, 85, 125 and 150 cm), a closer look at the higher degree of decomposition of the material (Von Post as high as 7) along with a lack of peatland plant species pushed our team to classify these sites as swamps rather than fens.

Exploring the soil in wetlands can be very helpful in determining the wetland class, but it is always best to view soil results alongside other wetland indicators like vegetation. What can be said is that it’s never a dull day in swamp town!